Students are frequently asked to analyze poetry. This can be challenging, and can also reduce enjoyment of this genre. Part of the reason for that, I think, is that students worry that they’re not going to come up with the “correct” analysis.

It’s important to remember that it’s really only in a testing situation that such a thing matters. In that case, the object of the “game” is to come up with a response that is likely to make sense to the person or computer doing the scoring.

People understand literary writing in their own ways. That’s actually a good thing, especially if you can explain why you reached your conclusion - backing it up with evidence from the text.

Below you will find some poetry analysis pointers and some poems on which to try them.

1. After reading the poem silently to make some initial understanding for yourself, read it aloud – relying on the punctuation to help you pause and stop appropriately. (You don’t usually need to pause or stop just because a new line is starting – regardless of the use of upper case letters in some cases).

2. Take the title, if there is one, into consideration. Does it give you a mindset that helps you understand the body of the poem? If there is no title, why might the poet have made that choice?

Dream Variations

To fling my arms wide

In some place of the sun,

To whirl and to dance

Till the white day is done.

Then rest at cool evening

Beneath a tall tree

While night comes on gently,

Dark like me –

That is my dream!

To fling my arms wide

In the face of the sun,

Dance! Whirl! Whirl!

Till the quick day is done.

Rest at pale evening . . .

A tall, slim tree . . .

Night coming tenderly

Black like me.

Langston Hughes

3. Be prepared to read the poem multiple times – beyond just once silently and once aloud. Do you see additional possible meanings as you read it again and again?

4. Could you put the poem into your own words to tell someone about it?

Untitled

Dear March, come in!

How glad I am!

I looked for you before.

Put down your hat –

You must have walked –

How out of breath you are!

Dear March, how are you?

And the rest?

Did you leave Nature well?

Oh, March, come right upstairs with me,

I have so much to tell!

(excerpt) Emily Dickinson

5. Try guessing at what the poet’s intention might have been, but consider other possibilities, too.

The Red Wheelbarrow

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

William Carlos Williams

6. Does the poem have a speaker (other than the poet) – like a character in a book or play? Does that help you to understand?

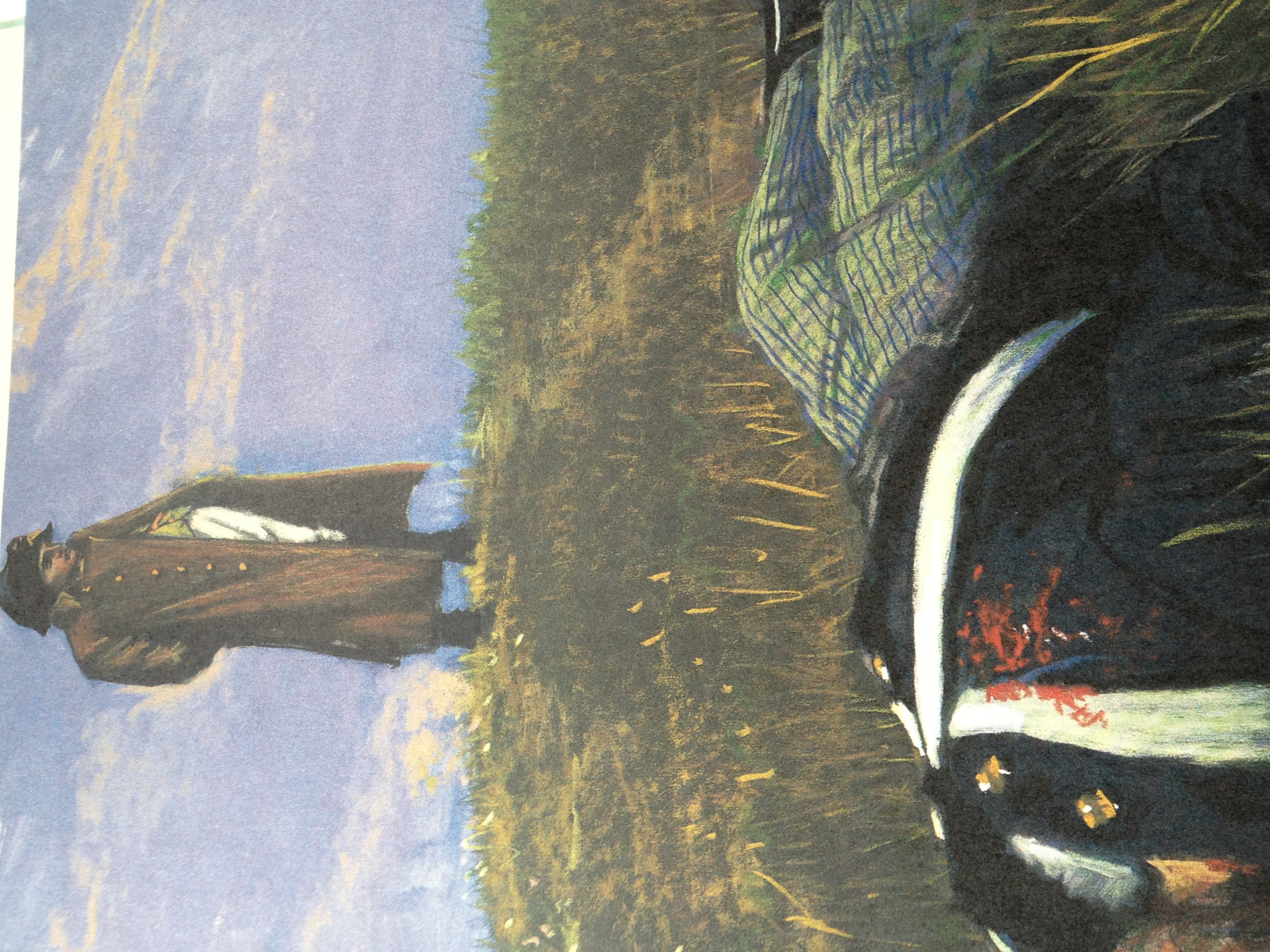

Incident of the French Camp

You know, we French stormed Ratisbon:

A mile or so away

On a little mound, Napoleon

Stood on our storming-day;

With neck out-thrust, you fancy how,

Legs wide, arms locked behind,

As if to balance the prone brow

Oppressive with its mind.

(excerpt) Robert Browning

7. Remember, every word or phrase probably means something; poets generally try not to use extras. That said, don’t worry if you encounter some unfamiliar words (or words you can pronounce used in unfamiliar ways).

Just like with any kind of reading, much meaning can be made without knowing every word. Don’t get too stuck. (Of course, if you will be reading aloud for an audience, you will want to be fully prepared).

A Time to Talk

When a friend calls to me from the road

And slows his horse to a meaning walk,

I don’t stand still and look around

On all the hills I haven’t hoed,

And shout from where I am, “What is it?”

No, not as there is a time to talk.

I thrust my hoe in the mellow ground,

Blade-end up and five feet tall,

And plod: I go up to the stone wall

For a friendly visit.

Robert Frost

8. Some poems aren’t meant to have definite endings or meanings; they are more open-ended and lend themselves well to personal interpretation – and that’s OK. (If you can’t ask the poet what he/she meant, it’s really not possible to know for certain, right?)

Untitled

A young man going to war

Gave me his hand

And in it

I found

A yellow bracelet.

Cheyene-Arapaho (author unknown)